Handicraft (overview)

Categories /

Economy/Industry

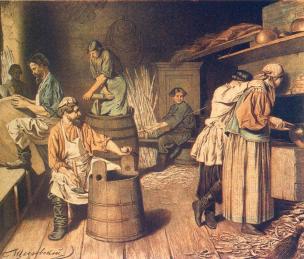

HANDICRAFT, an important part of St. Petersburg economy in the 18th to the early 20th centuries, started developing soon after the city was founded as craftsmen were coming here from various handicraft centres of the country. The decree issued by Peter the Great in 1722 prescribed that craftsmen should be divided into shops according to their trade in order to improve craftsmanship and the quality of their products. There were 24 shops registered in St. Petersburg in 1724 including food manufacturers, the largest in number, accounting for 48% of all craftsmen; clothes and shoe manufacturers (25 %); as well as blacksmiths, metalworkers, coppersmiths, woodworkers, potters, silversmiths, goldsmiths, etc. Workshops were small, usually consisting of a craftsman and his family members. Journeymen and apprentices were seldom employed. The City Charter of Rights was issued in 1785 wherein it was confirmed that craftsmen should register in their shops. There were 56 shops in St. Petersburg in 1789; fur makers, hatters, cappers, glovers, and boot-makers worked separately from tailors and shoemakers. As the city grew, a shop of stonemasons was set up. Wallpaper makers, bookbinders, and watchmakers were the other groups of craftsmen working in the city. The Handicraft Council was in charge of craftsmen's activities. The Council reported to the City Duma. Numerous foreign craftsmen organised their own shops with their own Handicraft Council at the head, the latter in existence till 1915. Merchants were granted the right to open their own workshops in 1815. Since then anyone who had learned a handicraft at a higher educational institution or taken a special course could open their own workshop. Because of that there were more workshops and craftsmen than the number of those registered in the Handicraft Council. Another group of craftsmen, which grew with time, produced science and art related goods such as musical instruments, medical appliances, optical devices, etc. Foreign jewellers, cart-wrights, haberdashers, and brewers were highly rated. Although shops decreased in number in the early-to-mid 19th century, each shop united craftsmen of various trades. While 23 shops numbered craftsmen of over 100 trades in 1867, there were over 115 of them in eight shops at the turn of the 19th century. The bakers and confectioners were the largest group; it also included makers of sausages, macaroni, mustard, and kvass. Bakers and confectioners were divided, in their turn, into makers of bread, loafs, kalach, baranka, macaroni, cakes, marshmallow, and pies. Although small workshops still prevailed as was the case with old handicrafts, larger workshops tended to grow in number. The well-known N. A. Andreev's bakery, for example, employed 66 journeymen and 24 apprentices in the late 19th century. A group of large bakeries covered about two thirds of bread and candy manufacture in the 1900s. The shop of tailors included furriers, glovers, hatters, and cappers. They specialised in their particular trade. Men's tailors, for example, were divided into tails makers, trousers makers, etc. Uniform makers formed a separate group of tailors. Women's tailors were divided into piece-workers, skirt makers, and jacket and bodice makers. Other tailors specialised in underwear. Tailors usually catered to specific groups; some shops served the rich, while other shops worked for the ordinary people. Some workshops employed from 100 to 200 and even more workers. Goldsmiths and silversmiths stood out from among St. Petersburg craftsmen, manufacturing jewels, ornaments, plates and dishes, etc. Furniture makers and shoemakers were also renowned; their products were frequently exhibited at Russian and international fairs and awarded numerous prizes. Although craftsmen of St. Petersburg mainly supplied the local market, some of their products were also exported to other regions. The handicraft industry, though losing somewhat to manufacturing industries, continued to play an important role in St. Petersburg economy in the early 20th century, and craftsmen made up a significant part of the capital's population. The Handicraft Council had over 11,000 workshops under control in 1910, which employed roughly 56,000 people, less unregistered craftsmen, foreigners and their family members. Handicraft also played a significant role in the city economy after October 1917 but it lost its major founding principle - independence - after the state had taken complete control of the industry.

Reference: Юнгар С. Финляндские ремесленники в С.-Петербурге // Ремесло и мануфактура в России, Финляндии, Прибалтике. Л., 1975. С. 90-99; Юхнева Н. В. Этнический состав и этносоциальная структура населения Петербурга, вторая половина XIX - нач. XX в.: Стат. анализ. Л., 1984. С. 56-65; Репина А. В. Немецкие булочники в Санкт-Петербурге // Немцы в России: Петерб. немцы. СПб., 1999. С. 197-204.

V. S. Solomko.

Persons

Andreev N.A.

Peter I, Emperor